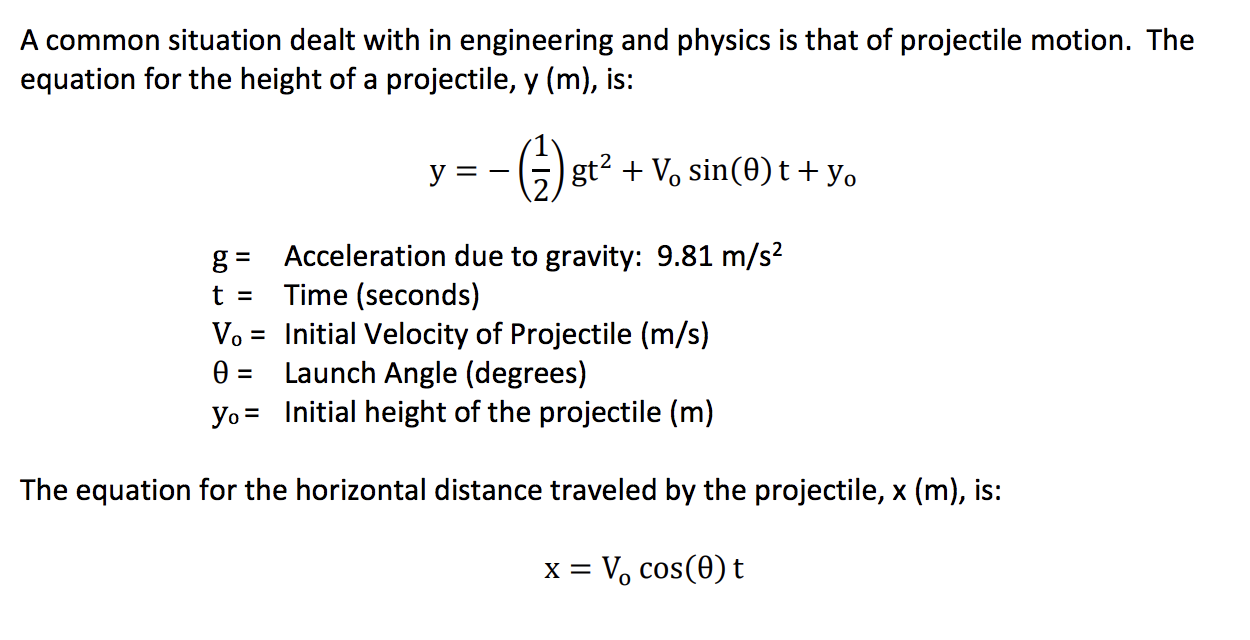

Start with the fact that, acceleration is the rate of change of velocity with time. I also neglect air resistance to make things easier. Since the mass of the ball does not change we only have to consider the acceleration due to gravity (-9.8 m/s 2). I started with the fact that once the ball is released, the only force acting on it is the force of gravity. The elevations measured off the photographs were then used to calculate the release velocity, time between snapshots, and maximum height of the ball. The size of the reference whiteboard, in pixels, was used to calculate the height of the soccer ball in meters. The images were loaded onto a computer, and the program GIMP was used to determine the distance, in pixels, from the ground to the projectile. The procedure was repeated several times, but only one trail was used in this analysis. The distance from the camera to the person throwing the ball (and to the whiteboard) were not measured. The camera’s shutterspeed was 1/250th of a second. The ball was thrown vertically by a student standing next to the whiteboard (see Figure 1) while pictures were taken. The whiteboard was leant vertically against the post of the soccer goal. We took the reference whiteboard (1.21 m tall), a soccer ball, and the camera outside. While this procedure probably goes a little beyond what I expect from the typical high school physics student, more advanced students who are taking calculus might benefit. Even the easiest way of solving this problem is not trivial, in fact, I ended up resorting to Excel’s iterative solver to find the answers. However, I was wondering if they could use just the elevation data to back out the Δt. Since the lab reports are due on Monday, and it’s the weekend now I’m curious to see what they come up with. Unfortunately, I think my students forgot to do the pictures of the stopwatch to get Δt, the time between each photograph. Table showing the conversion of the height of the ball in pixels to elevation (in meters). 1.22 m = 51 px) we can convert the heights of the ball from pixels to meters: Table 1. The reference whiteboard is four feet tall (1.22 m) in real life, but 51 pixels tall in the image. After all, the average velocity of the ball between two images would be: Now the easy way of getting the velocity data would be to estimate the heights (h) of the ball from the image using some sort of known reference (in this case the whiteboard), and determine the time between each photograph (Δt) by photographing a stopwatch using the same shutterspeed settings. A digital video camera with a detailed timestamp would have been ideal, but we did not have one available at the time. I offered my old, digital Pentax SLR that can take up to seven pictures in quick sequence and be set to fully manual. One of physics lab assignments I gave my students was to see if students could use a camera to capture a sequence of images of a projectile, plot the elevation of the projectile from the photographs, determine the constants in the parabolic equation for the height of the projectile, and, in so doing, determine the velocity at which the projectile was launched.

Calculated elevation of the soccer ball after launch. There are much easier ways of doing this, which we did not do. The problem was solved numerically using MS Excel’s Solver function.

ADVANCED PROJECTILE MOTION EQUATIONS SERIES

\(a = \left( \) -(6)Īfter combining (2), (3), (4), (5) and (6) and solving them we get n = 4.A series of still photographs of a projectile (soccer ball) in motion were used to determine the equation for the height of the ball ( h(t) = 4.9 t 2 + 14.2 t + 1.25), the initial velocity of the ball (14.2 m), the maximum height of the ball (11.6 m), and the time between each photograph (0.41 s). Putting these values in equation (1) we get Where \(R\) is the range of the parabola. Let us just assume that both the outer walls are equal in height say \(h\) and they are at equal distance \(x\) from the end points of the parabolic trajectory as can be shown below in the figure.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)